10 RAILROAD TYCOONS: THE GOOD, BAD, & QUESTIONABLE PIONEERS OF THE RAILROAD INDUSTRY

Between 1860 and 1900, the rate of railroad construction was increasing faster than ever. But what led to the rapid development of our railways?

That answer depends on who you ask. Certainly, innovation was a driving factor, but looking back, many would argue that the driving force for railroad tycoons was money and power.

While their impact on American history at the time was novel, many early railroad tycoons earned a reputation for being greedy monopolists who exploited the working class.

Let’s explore how the efforts of 10 famous — and in some cases, infamous — railroad tycoons in the late 1800s led to advancements in the railroad industry and changed America forever.

What Is A Railroad Tycoon?

By definition, a tycoon is someone who possesses power and wealth within a certain industry. Therefore, a railroad tycoon is a wealthy, influential person in the railroad industry.

We’ll also use the terms “tycoon,” “magnate,” and “mogul” synonymously throughout this blog to describe the historical figures in the railroad industry.

Famous Railroad Tycoons

Here are 10 good, bad, and questionable railroad tycoons of the past.

The Good

Though most railroad magnates get a bad reputation, there was one industrialist whose business efforts were considered pure.

James J. Hill

James Hill, the father of the Great Northern Railway Company, is best known for his visionary leadership of expanding railroad operations through the Red River Valley.

Following the Civil War, Hill landed work at the St. Paul & Pacific Railroad company, where he built a fuel business, swapping wood with coal to power steam engines. This business quickly made him a wealthy man, but unlike some other railroad tycoons, Hill was interested in more than just personal prosperity.

He wanted to develop the Red River Valley region, which was only accessible by boat at the time. After buying out the bankrupt St. Paul & Pacific, he and his business partners expanded the tracks to reach local markets from Minneapolis to St. Paul.

The tracks created an opportunity for new settlements in unpopulated areas — which Hill had a hand in, of course, offering train tickets to Swedish & Norwegian immigrants who agreed to settle along the route.

Overall, his contributions to the railroad industry were driven by more than just personal gain. He represents community and economic development.

The Questionable

These railroad moguls were innovative businessmen, but their links to unruly robber barons muddled their reputations.

The “Big Four”: Collis P. Huntington, Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker

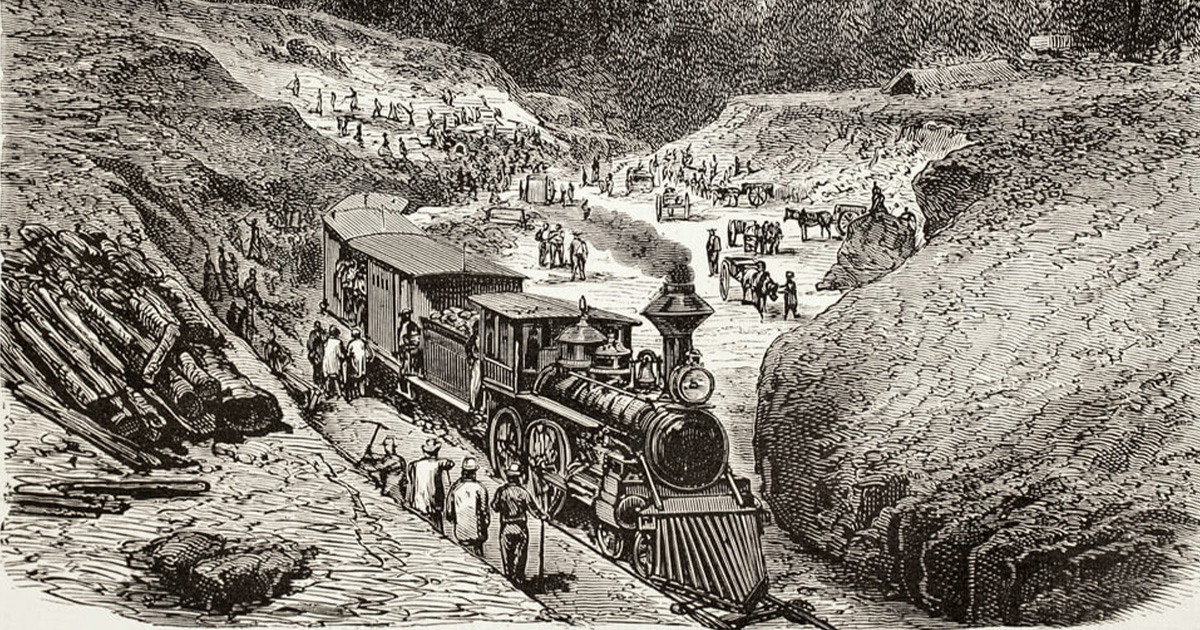

The “Big Four” —Collis P. Huntington, Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins, & Charles Crocker — founded the Central Pacific Railroad. Most notably, they’re remembered for building part of the first transcontinental railway.

Before the Big Four came into existence, Hopkins and Huntington were business associates. Hopkins built a business selling gold mining hardware in Placerville, California. He opened a second shop a few years later in Sacramento, where he eventually met Huntington.

Together, they created “Huntington & Hopkins,” the most successful mercantile house in the state for many years.

They came into business with Stanford and Crocker 6 years later through Theodore Dehone Judah, the engineer who conceived the idea and surveyed the land for the transcontinental railway.

He recruited Hopkins and Huntington to join forces with Stanford and Crocker to start building the rail line. They agreed to the task and in June of 1861 onward, they served as the directors of the Central Pacific Railroad where they earned the nickname “The Big Four.”

Huntington served as the company’s political and financial lobbyist in the East, and Stanford performed similar duties in the West. Cocker oversaw construction procedures, and Hopkin’s thriftiness earned him his spot as company treasurer.

With financial support from the government in the Pacific Railway Act of 1862, the Big Four were granted permission to expand the Central Pacific railways east of Sacramento.

Their impact on westward expansion is one of the greatest in American history, but their use of legal loopholes to gain government funding and their exploitation of Chinese laborers makes their work as railroad tycoons questionable.

Andrew Carnegie

Remembered as the “father of the American Steel Industry,” Andrew Carnegie landed his first railroad job in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in the 1850s. He served as a messenger in the telegraph office and, later, the secretary and telegraph operator for the Pennsylvania Railroad’s superintendent of the Pittsburgh division.

In the 1870s, he opened his first steel company, the “Keystone Bridge Company.” Here, his goal was to replace wooden rail lines with steel, improving the safety and efficiency of tracks. By the 20th century, he was the wealthiest man in the US.

But like many other railroad magnates, his reputation wasn’t devoid of corrupt practices. He’s infamously known for the violent Homestead Strike in 1892, where unhappy steel workers protested wage cuts from the company.

Overseas at the time, Carnegie placed his general manager Henry Clay Frick in charge. Escalating the situation, Frick locked workers out of the plant and called in armed soldiers to guard the building. Eventually, a bloody scuffle broke out leaving 10 men killed.

Though he wasn’t directly responsible, many held him to be because of his trust in Frick and his silence in the matter. With his reputation marred, his business struggled, ultimately leading to him selling the company.

From there forward, Carnegie devoted his life to philanthropy, giving away over $350 million dollars before he died — an act that remarkably restored his reputation in a way no other early railroad tycoon was able to do.

The Bad

Though their impact on the industry is undeniable, these men and their business practices paint them as the most infamous railroad tycoons of the century.

Cornelius Vanderbilt

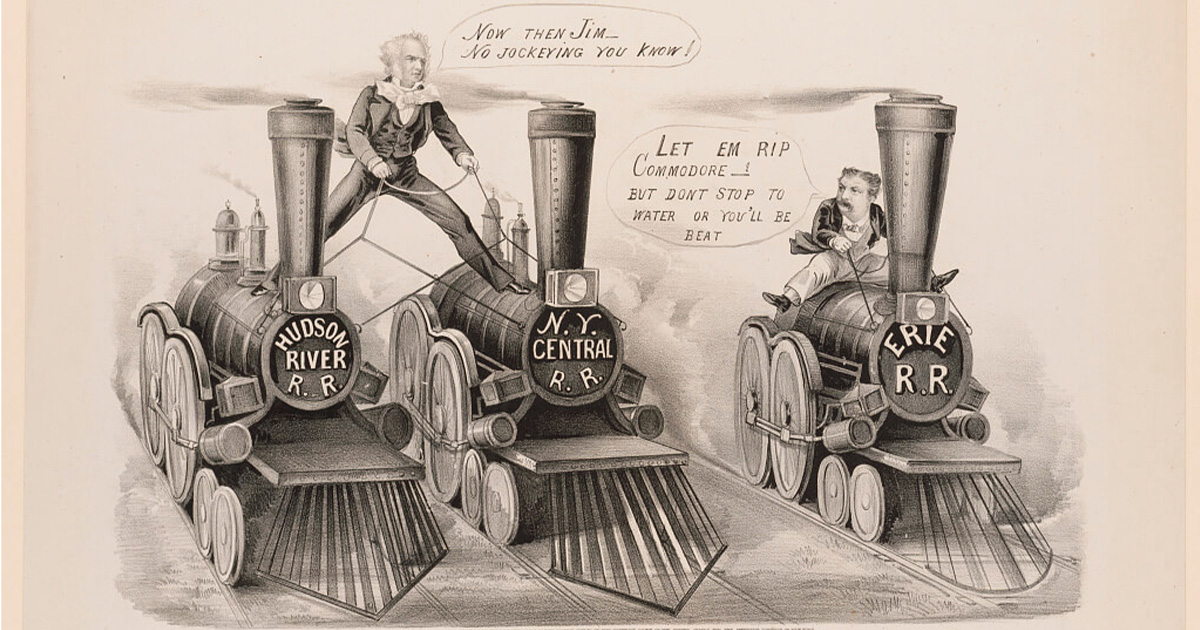

Like many other railroad industrialists, Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt started his career in the steamboat industry. He was such a force that his biggest competitors paid him to not challenge their business.

In 1863, he entered the railroad industry by taking control of the New York & Harlem Railroad (NY&H). For the rest of his career, he bought and merged companies together, monopolizing ownership of rail lines from the east coast to Chicago.

Wanting to expand his empire further, the Commodore set his sights on the Erie, the longest rail line in the world at the time. He was duped by fellow traders James Fisk, Jay Gould, and Daniel Drew into purchasing $7 million of fake, watered-down shares.

Jay Gould

It wasn’t just Cornelius Vanderbilt that Jay Gould swindled. Gould has a long history of disregarding laws and manipulating stocks — and when caught, bribing government and law officials to avoid prison time.

He made a name for himself by buying and selling stocks and bonds in the railroad. Eventually, he controlled one in every six miles of American railroads.

Through master manipulation and a money-hungry attitude, Gould became one of the richest men on Wall Street. But his notoriety made him extremely unpopular, with some sources calling him one of the “most hated men” in American history.

Russell Sage

Russell Sage’s greatest contribution to the railroad industry was introducing telegraph systems within railways. Working with Jay Gould, he organized the Atlantic & Pacific Telegraph Co.

He got into the stock market through a loan to Wisconsin’s railroad in an effort to save the La Crosse Railroad. To protect his investment, he purchased a majority of the shares and became vice president of the railroad.

From there on, he put his energy into the stock market, where he inevitably crossed paths with Jay Gould. Through stock market “puts and calls” and manipulation of securities, he and Gould illegally took control of the New York City rail lines.

Cyrus Field

The inventor of the transatlantic telegraph cable, Cyrus Field created one of the most profound communications systems of the industrial revolution. He solved the issue of international communications using undersea cables to messages across the Atlantic Ocean in a matter of minutes.

Naturally, his invention pushed him into extreme wealth. He ventured into the stock market, investing in the New York Lines where he came into business with Gould and Sage. He was later double-crossed by Gould and Sage, draining his wealth and tarnishing his reputation for good.

Railways Are A Booming Industry… But At What Cost?

Looking back, most railroad moguls got rich through intimidation, manipulation, violence, and blatant fraud.

But despite these immoral practices, their collective efforts led to immense advancements in the rail industry and opened the door for cross-country travel — an idea that formerly only the rich could fathom.

Strasburg Rail Road’s Famous Tycoons

Strasburg Rail Road has some famous railroad tycoons of our own. In the late 1950s, a small group of rail enthusiasts, including Henry K. Long and Donald E. L. Hallock, purchased the struggling Strasburg Rail Road to revive tourist passenger services.

Within the first year, ridership reached close to 9,000 passengers; within three, 125,000. Since then, Strasburg Rail Road has been a flourishing passenger railway that offers the unique opportunity to ride aboard a restored steam locomotive.

Today, Strasburg Rail Road offers a range of steam train experiences, including seasonal and holiday trains, dining trains, and entertainment trains.

Book tickets to Strasburg Rail Road to glide along the tracks of America’s oldest continuously operating railroad.

Go behind the scenes on a tour of our renowned mechanical shop and learn all about how we build and refurbish our historic trains!

Go behind the scenes on a tour of our renowned mechanical shop and learn all about how we build and refurbish our historic trains!